Ecofeminism

according to Vandana Shiva and Maria Mies

Anna and the Grabbing Back team

We are aware that Vandana Shiva has affiliations with Russell Brand, who has been accused of sexual assault by several women. We firmly stand with and believe the victims speaking out against Russell Brand and the systems that enabled him. In order to understand where we are with Ecofeminism today, we believe explaining her initial ideas on the topic is important. We do not stand behind everything she has stated or her current beliefs.

As with all of our articles, we are choosing to unpack theories that we think have had an important impact on making feminist movements today what they are. That doesn’t mean the Grabbing Back collective actively endorses the theories or academics behind them.

This article is an explainer of the 1993 book Ecofeminism, written by activists Vandana Shiva and Maria Mies. Their work had a big influence in shaping the ecofeminist movement, and although the modern movement has grown and gone in new directions, this book is important in understanding its roots.

‘Ecofeminism’ was a bit of a mystery to me before I read this book. I thought perhaps it meant being an environmentalist and a feminist, or maybe a fluffy, loose-leaf, tree-hugger type (like me). Turns out, when Shiva and Mies are writing about it, eco-feminism is a thoughtful political stance and wide-reaching worldview. They see all living things as one organism, they respect Mother Nature more than you respect your mother Janet, and put their hope in this thing called ‘subsistence living’ – we’ll come to that shortly.

The Big Bad: capitalist-patriarchy

Ecofeminism, according to Mies and Shiva, understands all things to be connected and interdependent. In particular, it draws a very close relationship between women and Mother Nature, and says that they both experience analogous violence. They also argue that there is a single, common cause of this violence - the ‘Big Bad’ so to speak. They refer to it as ‘capitalist-patriarchy.’

Vandana Shiva. Source: Sanctuary Nature Foundation

In their book, capitalist-patriarchy is a force that is characterised by dominance, violence, exploitation, intrusion, and unlimited growth. In stark contrast, the force behind both nature’s way and women’s lives is understood as reproductive, regenerative, life-giving, autonomous, and symbiotic. We’re going to call this second force ‘subsistence living’ and go into more detail shortly.

It might already sound strange to make such grand statements about women and nature, but remember, this book is an overarching framework - it’s almost an answer to The Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything. I called capitalist patriarchy a force, because it seems that for Shiva and Mies, it’s a way of life, as well as a conceptual framework and the way our economy behaves. It frames everything from the cornerstone of how we currently practise science and technology, our moral value system, all the way down to part of our individual psyches. The same goes for subsistence ways of being - Mother Earth’s way.

I found it easier to grasp the contrast they were drawing in relation to nature’s way and capitalism’s way. The most extreme version of capitalism is concerned with constant increasing growth - more wealth, more of a product, higher GDP. These things are often painted as leading to a higher quality of life. There is no consideration of a possible cap on growth, and there is often lots of waste produced. In (this extreme version of) capitalism, people want and expect to be able to live with no limits. According to this ‘no limits’ rule, there can always be more food, more clothes, more plastic fidget spinners, more of anything for the right price.

In contrast, there is a capped growth on almost everything in nature in order to keep all things in balance; in a rainforest, one kind of tree cannot take up more space eternally, otherwise there will be no room for others. Capitalism is concerned with everlasting linear progression, whereas nature is concerned with everlasting cycles. Capitalism is concerned with needing more, nature is concerned with having enough.

Mies and Shiva relate women to subsistence ways of being for at least two reasons: (1) they see birth as one of the ultimate regenerative and life-giving cycles and (2) they believe that because of patriarchy, women spend much more of their lives doing the kind of work that relates to these regenerative, cyclical processes. Where men are more likely to be factory workers creating products for wages, women are more likely to be tending to children, growing food to eat. Remember, Shiva and Mies were speaking on a global scale, even if that won’t feel relatable for some of us women in very urban contexts.

Violence against Mother Nature and violence against women

In their understanding of the world, the capitalist-patriarchy and subsistence ways of being are in direct opposition. At the moment, capitalist-patriarchy is winning - with disastrous consequences. The authors see this as the common cause for analogous violence experienced by both women and nature. Mies and Shiva often use the word ‘violence,’ but it’s worth noting that they use it in a more general way to how I would in my everyday speech. Rather than necessarily meaning a physical confrontation, they mean directed oppression - we’ll go through some examples shortly.

They often use violent language to describe humanity’s treatment of nature and women; Shiva in particular is sometimes criticised for this, but from what I can tell, I think she really feels that the affronts to nature are so despicable that only that language is appropriate. You’ll have to make up your own mind.

Here are two quick examples of ways that capitalist-patriarchy directs analogous violence towards women and nature:

1.Under capitalist-patriarchy, both women and Mother Nature’s labour have no value.

Subsistence farming means growing food in order to eat it yourself; a local, regenerative cycle. This is in contrast to farming much more food than you need to sell in order to gain a financial profit. Subsistence farming is much more in tune with nature’s way of working - we have to change environments and landscapes to farm on a scale large enough to sell for profit. However, GDP, often used as shorthand for ‘how well a country is doing,’ has no way of measuring subsistence farming, it only measures profit. This kind of labour has no value under capitalist-patriarchy. This is analogous for women, not only because women play such a large part in subsistence farming, but because the same is true for raising children. Giving birth and raising children is not considered valuable labour, it is a regenerative cycle with no net profit gain.

2. Under capitalist-patriarchy, both women and Mother Earth experience violent intrusion via technology.

Mies and Shiva argue that we should be deeply suspicious and resistant of the ways that technology can be used to adjust nature to better fit the desires of capitalist-patriarchy. They compare farming technologies like genetically modified (GM) crops to reproductive technologies like IVF, abortion, and screening.

GM crops have had their DNA edited so that their desirable characteristics are increased. The new strain of crop is often patented, meaning that for local farmers to plant them, they must pay massive corporations for the rights to the seeds. Shiva believes that this is dominating, intrusive and violent towards nature - all for the sake of profit.

Mies argues that this is comparable to the way reproductive technologies are used under capitalist-patriarchy. She argues that despite what we’re told, they’re used to control populations and dictate which kinds of human beings are allowed to exist. Mies believes that this is dominating, intrusive and violent towards women - also for the sake of profit.

It’s a sharp analogy, and one that I certainly found uncomfortable. It’s important to quickly note two things. First, Mies wants people to have access to abortion, but believes that this technology, under capitalist-patriarchy, is used as a weapon against women. Secondly, the authors are very highly critical of science and technology used under capitalist-patriarchy, but do propose ways that science and tech could be reformed.

A false hope: charity under capitalist-patriarchy can’t create change

One of the central points Mies and Shiva make is that under this framework of capitalist-patriarchy, even what we are calling ‘progress’ or ‘development,’ and considering good and hopeful, is actually destructive. In the chapter entitled The Myth of Catching Up Development, they unpack this.

‘Catching Up Development’ is a framework that proposes that the Global North, for a series of reasons, is ahead of the game. It has already developed, it is living at a high quality of life, and sets a standard to be aspired to. Countries in the Global South, however, are still ‘catching up,’ as implied by the now out-of-date term ‘developing countries.’ They might be depicted in caricatures as archaic, sometimes even so far as less evolved: intellectually, morally, and economically.

There are forms of this framework that are very obviously racist and rooted in colonial narratives, but there are also kind and well-intentioned ways that we engage in this narrative. Red Nose Day raises money for very important work, but the underlying framework suggests that we’re providing charity now so that ‘developing countries’ can ‘catch up.’

They argue that this framework is a myth for two reasons. Firstly, so-called ‘development’ as modelled by the Global North is not desirable. It is true that in the Global North, many people are able to live by the ‘no limits’ rule we introduced earlier, and this certainly feels luxurious. However, in the same countries, rates of violence against women remain, and, Shiva and Mies argue, although people might own property, they tend to be completely alienated from their own land.

Rubbish mountains in Deonar, India. Source: BBC

Secondly, reaching this ‘developed’ status is literally impossible for the Global South. This is because the ‘quality of life’ at which the Global North currently lives was only made possible through exploitation of people and land in the Global South. Resources were plundered from overseas, labour was done overseas by cheap or enslaved workers, products then shipped to the Global North, used, thrown away, and garbage heaps shipped right back overseas again. The ‘no limits’ rule by which the Global North lives is actually a massive lie. There are limits, but the Global North ships the impending edge of those limits overseas. Living by the ‘no limits’ rule requires you to have land and people to exploit, who pay the cost; somewhere to ship to. For the Global South to be able to live by the ‘no limits’ rule, it would have to be just as exploitative, but because the world, both people and planet, is reaching the end of its limit, there is no room for that further exploitation. There can be no ‘catching up.’

Their solution: the subsistence perspective and tree-hugger types

Instead of this false hope in the myth of catching up development, Shiva and Mies hold that we must put our hope in the subsistence perspective - in the way of life modelled to us by nature, that works in tune with nature.

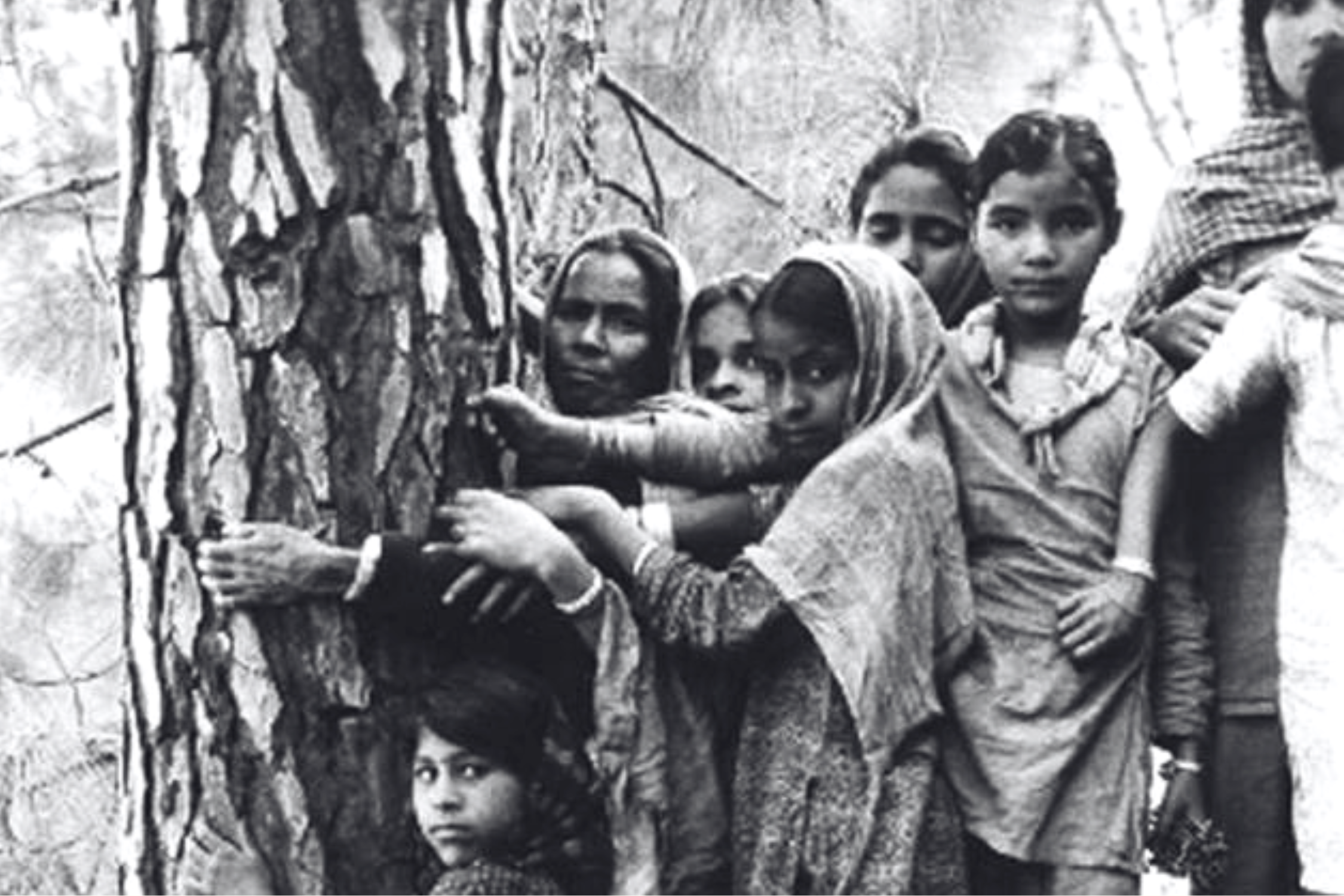

The only thing I understood correctly before I read up on eco-feminism was that these certainly are the politics of the tree-hugger types. I thought the phrase ‘tree-hugger’ probably came from weed-fuelled Woodstock fest; I couldn’t have been more wrong. Turns out, in her twenties, Vandana Shiva was reporting to the world about the women of the Chipko Movement, which was kicking off in the 1970s in the Indian Himalayas. The women of the Chipko Movement literally hugged trees to stop them being cut down. In doing so, they were defending their livelihoods, their ability to live a subsistence lifestyle, as well as Mother Nature and her rights. There’s a short video documentary at the bottom of this article that I really recommend you watch.

Images of the Chipko women. Source: Feminism in India

Shiva interviews some Chipko women in the book. They say the three most important things to them are their freedom, the forrests, and food. It’s interesting hearing them talk about freedom; they seem to want to reject any notion of dependence on global markets, or even money at all. Instead they gain their sense of freedom through dependence on nature, themselves, and their small local communities.

I think that’s a key element of the spirit of subsistence ways of life that Shiva and Mies put their hope in. They believe that the needs of any person can be met in this way of life: the need for food can be satisfied by the local land; the need for identity can be satisfied by the local community; the need for affection, protection and freedom can be satisfied by spending time playing with children. The central idea is that we don’t need capitalism or consumerism, we don’t need to buy things to meet our needs - we can live well with what nature and local community provide. For Mies and Shiva this isn’t just a potential paradise, but also the only possible way of us living in peace.

At the end of their book, they write a manifesto for subsistence living. This way of living disregards hoarding commodities and instead considers its most important activity to be “the creation and recreation of life.” They want to make things in order to use them rather than to sell them. They call for renewed relationships with nature, and between men and women, founded in respect. They desire grassroots democracy, a deep acceptance of our interconnectedness. They want new principles for practising science and technology, a reformulation of what work is and what it's for. They want for our common home - water, air, soil, resources - to be seen as nature’s gifts for us to protect and restore and share.

Finally, they address whether their utopia is even a feminist project at all. They conclude it is; it requires men to give up the lie of unlimited growth and the exploitation required to prop up the lie. It requires them instead to join women in the work of tending to limited, sufficient, cycles of life.

This article was an explainer of Shiva and Mies’ theory, but as you might have noticed, we didn’t evaluate it very much throughout. We’d love to hear what you think of their ideas! We just wanted to make one quick evaluative note:

This theory values at least some versions of femininity, and connects this with women being able to give birth. For us, feminist theory needs to include trans- and cis- women with all kinds of bodies and gender expressions. Listen to our podcast episode for Series 2 Topic 2 to hear more discussions of eco-feminism and trans-inclusion, and check out our podcast episode for Series 2 Topic 1 for more discussion of womanhood, behaviour, and bodies.

References and reading list

Check out this video clip from the documentary The Seeds of Vandana Shiva about the Chipko Movement:

Check out all this epic content on ecofeminism from Feminism in India. Feminism in India is an online platform that publishes content about feminism in India (clue’s in the name!)

Much like Grabbing Back, they started up because they found that the feminist theory they could get their hands on tended to be academic articles which were dense, theoretical and mostly behind a paywall. They create accessible content with the hope of creating a generation of young people that are aware and educated about feminism and social justice.

Their content on Shiva and the Chipko movement is great - highly recommend.