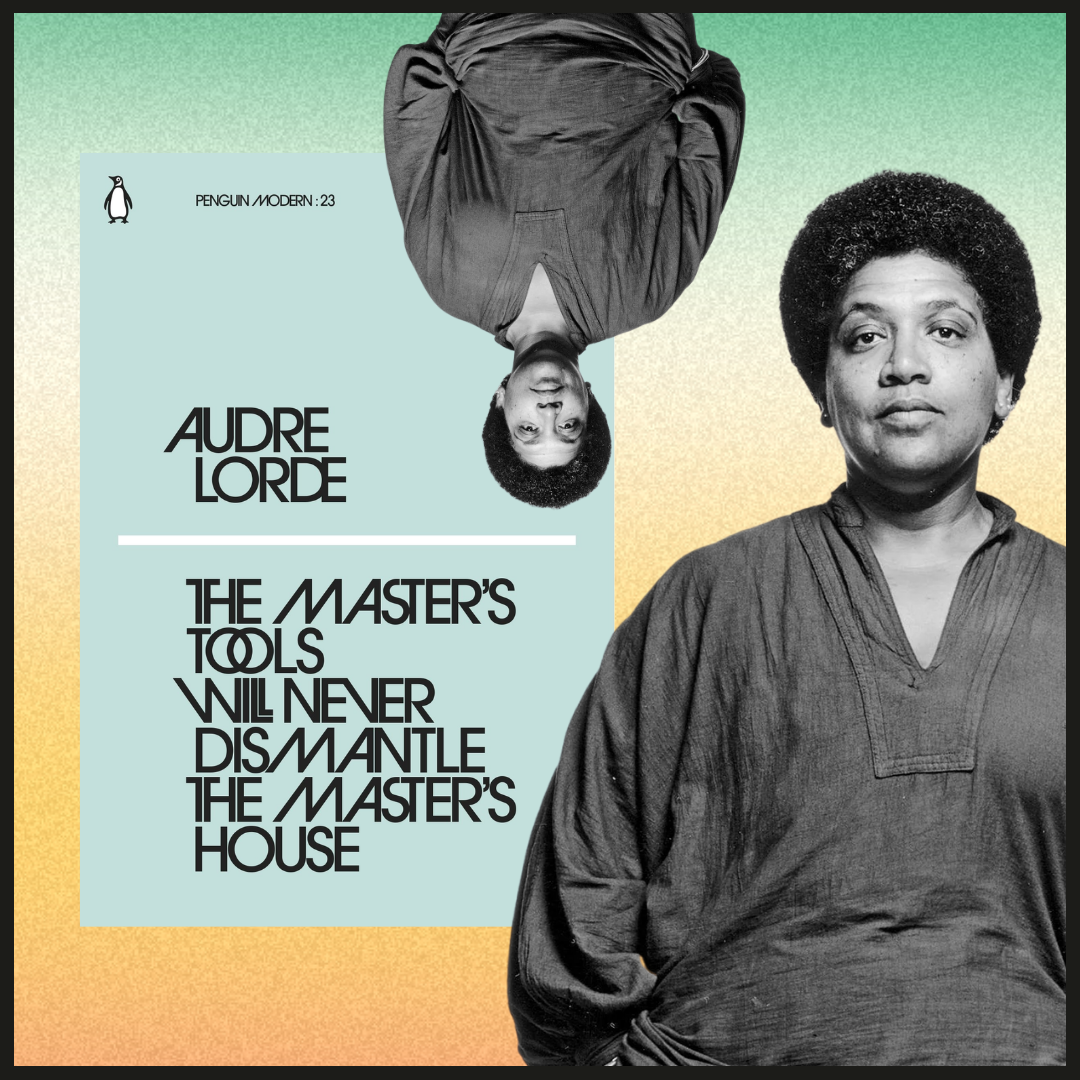

Audre Lorde: The Master’s Tools

When will we learn? When will feminism own up to its problems?

Cyara Buchuck-Wilsenach

This article is written about Audre Lorde’s book, ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master’s House,’ written in 1984..

You can find the book in the following places:

City central libraries will likely have a copy

If you’re stuck, drop us an Instagram DM and we’ll see what we can find

Terms in bold and green are defined at the bottom.

There are some books about which it feels entirely pointless to write a single word. How could I possibly do justice to the ideas expressed? ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’ by Audre Lorde is one of those books.

Lorde’s Argument

The words Lorde wrote in the 70s and 80s ring as urgent, necessary, and true today as I can only imagine they did when she first wrote them. In many ways this is a great shame; it begs the question, what has changed? What progress, what liberation has been achieved? Though we have made some small steps towards a more just and equal world, to say we have achieved justice and (true) equality would be a phenomenal lie: racism, sexism, and homophobia remain real conditions of all our lives in this place and time. If the feminist movement wants to see real change, we must own up to being part of the problem.

The issue at the root of this, is the question of who owns the tools to dismantle and destroy oppressive structures? If the answer is the master - those with power and influence bestowed on them by an unjust society - we might wonder how effective our efforts can ever be.

‘Better never means better for everyone, it always means worse for some.‘

A Handmaid’s Tale

Lorde, the ‘black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet’ who was born in the 1930s in New York, owned and lived her truth more than most people I’ve ever met. Perhaps this is part of why her work is so powerful; she doesn’t dilute her message. She says it as she sees it, and the way she saw it was that we all live in a society plagued by hierarchy and the search for power. When she talks about ‘the master’s tools’, she means the ways that people with power - particularly men - hold onto their power. The way they stop others from toppling the systems they rule because it wouldn’t help them. As Margaret Atwood put it in The Handmaid’s Tale; ‘better never means better for everyone, it always means worse for some’.

When Lorde wrote that these tools will never ‘dismantle the Master’s house’, she was referring, at the most basic level, to the fact that power, justice, equity, is never freely given away. It must always be wrested, challenged. As feminist and historian Sheila Rowbotham argued in her memoirs of the 1960’s; ‘At twenty-one I was convinced that parliament would never give socialism to you.’ But Lorde wasn’t talking about parliament or the Senate or other big political institutions. No, she was referring, largely, to feminist academics.

Feminist academia isn’t free from the world’s problems

“Racist feminism” continues to pervade feminist spaces, especially in the West. The recent debates and campaigns which have sought to dismantle the racist structures of our educational institutions - both schools and universities - pay service to this fact. The idea that we can ‘debate’ racism within the institutions that have served to create and uphold racist structures of oppression for most of their existence shows how far (or how little) we have come.

That a group of academics are expected by institutional authorities to calmly sit, debate, and theorise on major issues of which they have little or no personal experience exemplifies their limited understanding of the injustices faced by individuals within these institutions. The years-long campaign to remove the slave trader Cecil Rhodes’ statue from Oriel College, Oxford, is the most famous example of this. However, the dispute over Cecil Rhodes’ statue is far from the only ‘debate’ on race or feminism in academia and the wider public. Rather it is one example amongst many - it forms part of a much wider, and incredibly destructive, narrative our society has bought into; the notion that one’s rights and access to justice can and must be achieved through a calm, unemotional debate chaired by an ‘impartial’ figure (impartial in the sense that they have no personal experience of the issue, as if this means impartiality - it doesn’t).

Collage of photos from the South Africa and UK based ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ protests.

Feminist theory and academia have not escaped this realm of middle-class/white hegemony which disguises itself as fake impartiality. The problem here is clear - when the tools to overturn oppressive structures are owned by those institutions and individuals who benefit from them, progress is impossible.

Who held the power in feminist spaces of the past?

The problems outlined above show exactly what Lorde spoke and wrote on throughout her life. Lorde’s focus on racism, her experience as a lesbian and poor women, and the lessons she brought from the civil rights and Black liberations movements all clearly show the need for a model of intersectional liberation within feminism that prioritises poor, minority women. The book’s namesake essay begins with this (kinda obvious?) assumption:

“It is a particular arrogance to assume any discussion of feminist theory without examining our many differences, and without a significant input from poor women, Black and Third World women, and lesbians. And yet, I stand here as a Black feminist lesbian, having been invited to comment at the only panel [...] at this conference [...] where the input of Black feminists and lesbians is represented”

This quote was originally taken from Lorde’s speech at the 1978 conference at New York University. Recently, I attended the United Nations Women’s ‘Generation Equality Forum’. Coming out of it, my reflections were starkly similar to Lorde’s. Indigenous women, working-class and poor women, and young people were all excluded in various ways, and the digital nature ended up being really inaccessible to many. It showed me that over 40 years on - 2 whole generations - ‘the tools of a racist [and ableist] patriarchy are [being] used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy’.

These tools included the public silencing of two young feminist activists from the Global South, who were invited by the French government organisers to speaker in the prestigious closing ceremony. One girl had her mic turned off and was cut off just 60 seconds or so into her allotted 2 minutes, and another was left entirely out of the programme. In the same ceremony, with the same host, older, male, European government officials were given around 5+ minutes to speak, entirely uninterrupted, well beyond their allotted time frames. All this at a conference whose very name (‘ generation equality forum’) was meant to convey the importance of the generations born since the last major UN feminist conference held in 1995.

Reform vs. revolution: how do we change?

I have been an advocate for reform - for trying to change what you can, where you can, as much as you can, in the hopes of moving towards a fairer world by steps. However, reflecting on Lorde’s writing and considering the current world we live in - where we remain somewhere between 100-260 years away from achieving basic gender equality - I do wonder how much better a revolutionary liberation approach would be; does true liberation require a radical overhaul of our current system? As a jury I am still out on which route I will work towards. At times, these feel like two different viewpoints that lead to the same actions (see figure).

Either way, Lorde’s statement that ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’ rings as an eternal truth. I ask, reader, to answer this question: what progress, what liberation has been achieved since Lorde wrote her famous words? Can the words ‘progress’ and ‘liberation’ even be used together in one sentence?

Definitions and Footnotes

‘Oppressive structures’ - In simple terms, a structure is made up of social norms (how society says we should act and act in relation to each other) and the way our institutions are set up. Oppressive structures are those structures which give rise to oppression (for example, racism, sexism, and homophobia).

References

Rhodes Must Fall

Equal pay for women

Depending on how we measure ‘equality,’ reports vary: